Mama Comba’s Gombeau Story Info

- Title:

- Mama Comba’s Gombeau

- Date:

- 1764-09-04

- Story:

-

During the summer of 1764, members of the French Superior Council devoted several months to an investigation involving maroons, gatherings, and food. Testimony from Africans and their descendants enmeshed in this court case reveals how, despite the threat of punishment, enslaved and free Africans and people of African descent formed friendships, kinship, and community across boundaries imposed by enslavers. Established in 1724, the Code Noir of Louisiana “forbid slaves belonging to different masters to gather by day or by night.”1 Yet these efforts to contain movement, information, and people failed to keep individuals such as Mama Comba, Louison, Foÿ, Cézar, Fatima, and their associates from cooking, eating, and enjoying one another’s company together in the garden of Sieur Cantrelle.2 In particular, enslavers raised alarms over a feast involving “un gombeau,” the first mention of gumbo in the colonial archive.3

By the time Mama Comba testified for the second time, she had been incarcerated in the city’s prison and had remained there for nearly two months while awaiting trial. This was the case for all witnesses of African descent affiliated with the dinners. In Comba’s testimony, she negotiates telling the truth under oath with maintaining loyalty to her established community. Given that enslaved people were punished regardless of if they were found guilty, Comba recounts the events leading to the dinner freely, leaving out little details. It is evident in her account that she refuses the dehumanization written into the Code Noir when she highlights having a “good time” with Louison and the “many Bambara” that she had met at Cantrelle’s garden. Comba defends Louison, stating that Louison asked permission from her enslaver [Cantrelle] to host the supper. In doing so, Comba asserts the freedom of mobility and expression of enslaved people. She also claims her narrative, stating that the facts uttered in the interrogation were true for the record, yet she also articulates an act of refusal when she declines to make her mark before the court. Her testimony shows how she made sense of the events leading to the dinner, and communicates her agency in it all.

This particular case is also a testament to Comba’s connectivity to life and places beyond L’Hôpital des Pauvres where she stayed. Her testimony serves as an archival proof of her lived experience, of who was important to her and of what she enjoyed.4 The extent to which she, an enslaved woman, felt unashamed and unapologetic about her actions and the actions of her comrades reveals her unabashed defense of her humanity and her innocence within a legal system designed to make her guilty. She positions herself as someone who helps others in need, who is generous, and who is aware of what goes on around her. Although she identified herself as Julie dit Comba during her interrogation, her community and colonial administrators alike called her Mama Comba, proof of the reverence and respect she commanded.5

Further Resources

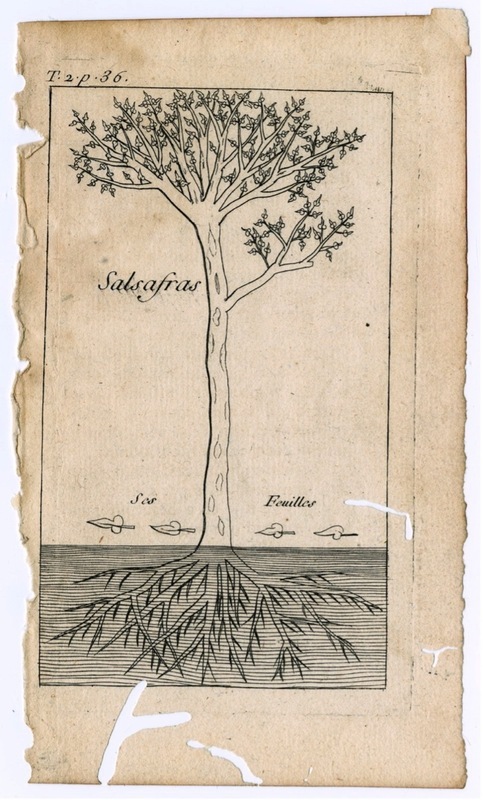

Fig. 1. Travel journal drawing of sassafras, a native plant to North America which is prepared and used as a medicine and, in cooking, as a seasoning and thickener by Indigenous peoples across the Gulf South. It is a central component of filé gombo. Gombo is a Louisiana Kréyòl word derived from the Bantu languages of West Africa, meaning “okra.” Source: Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, Histoire de la Louisiane, tome second (Paris: de Bure, 1758).Notes

-

“Article XIII. We likewise forbid slaves belonging to different masters to gather by day or by night, under the pretext of a wedding or any other reason, whether on their master’s property or elsewhere, and still less in the main roads or the out of the way places, on penalty of corporal punishment, which cannot be less than a whipping and [branding] of the fleur de lys; and in case of frequent repetition and other aggravating circumstances, they may be put to death, which we leave to the decision of the judges. We require all our subjects to pursue the offenders, and to arrest them, even though there is no order issued against them.” ↩

-

Historian Stephanie Camp first theorized how enslaved people, especially women, and enslavers competed over the same terrain in the plantation South. While enslavers attempted to contain enslaved people using surveillance systems, slave quarters, and legislation like the Code Noir, enslaved people created what she called a “rival geography,” or ways of reading the land and built environment that evaded containment and captivity. Stephanie Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004). ↩

-

Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992). ↩

-

For more on the medium of testimony and slave testimony in the archive of French colonial Louisiana, see Sophie White, Voices of the Enslaved: Love, Labor, and Longing in French Louisiana (Williamsburg: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2019). Mama Comba and Louison demonstrate the centrality of African women and women of African descent to sites of resistance, pleasure, and enjoyment in Louisiana. To learn more about Black women’s practices of freedom in Louisiana, see Jessica Marie Johnson, Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020). ↩

-

See the testimony of Louison in this document, https://lacolonialdocs.org/document/10603, and how French commissaire-ordonnateur Denis-Nicolas Foucault introduced Mama Comba during her first interrogation https://lacolonialdocs.org/document/10482. ↩

-

- Keywords:

- marronage kinship labor fugitivity rival geography play

- Latitude:

- 29.954

- Longitude:

- -90.066

- Documents:

- d0207