Biron Threatens the Future of the French Colony Story Info

- Title:

- Biron Threatens the Future of the French Colony

- Date:

- 1728-07

- Story:

-

Resistance to enslavement in Louisiana took many forms. For Biron of the Bambara nation, marronage became part of his everyday lived experience. We learn from the documents that Biron survived the Middle Passage on the ship Aurore, one of the twenty-three slave voyages from Africa to colonial Louisiana during the French regime. In Louisiana, Biron stole back his freedom frequently by running away from his enslaver’s plantation in the present-day Gentilly neighborhood of New Orleans. He also purportedly did not speak French, or pretended not to speak it. When he was caught by enslavers and forced to testify, Biron relied on Samba, another man of the Bambara nation, to translate for him before the Superior Council.

His marronage threatened not only his enslaver’s sense of control, but also that of the colonial administration. In his testimony, Biron described the everyday violence he experienced while enslaved in French Louisiana. In the face of recurrent assault, Biron ran away from his enslaver. Not the first time he went marron, Biron used the tactic of marronage frequently. Upon hearing the news that Biron took hold of his enslaver’s gun and that he escaped, the Attorney General of the colony asked members of the Superior Council to pursue Biron in a formal interrogation. In his letter to the members of the Council, the Attorney General emphasized how Biron’s self-defense (“rebellion contre son maitre”) in Gentilly represented a major threat to enslavers on distant plantations (“habitations eloignées”), especially as Africans increasingly made up a substantial portion of the community.

In the immediate years before and after Biron’s trial, French colonial administrators faced other threats to the future of the colony. Several months after the ship Aurore reached Louisiana, the Attorney General pursued the deaths of Native runaways who used armed resistance against enslavers and their allies.1 In November of 1729, just a year and a few months after Biron’s trial, Natchez warriors rose up against the French at Fort Rosalie, almost bringing the colony to collapse. In the wake of the Natchez wars, the French administration recorded two alleged conspiracies in 1731 led by Bamana people enslaved in Louisiana.2 These threats to French power contributed to the decision of the Company of the Indies to sell the colony back to France, effectively cutting Louisiana off from the transatlantic trade in Black life.3

Further Resources

Fig. 1.Map depicting the City of New Orleans and the Chantilly area where Biron was enslaved. Also shown is the portage from Bayou Saint-Jean to Lac Pontchartrain and the Chapitoulas estate. Source: Detail of François Saucier, Carte particulière d’une partie de la Louisianne ou les fleuve et rivierres [i.e. rivières] onts etés relevé a l’estime & les routtes [i.e. routes] par terre relevé & mesurées aux pas, par les Srs. Broutin, de Vergés, ingénieurs & Saucier dessinateur, map, 1749, Library of Congress, control #2003623383.

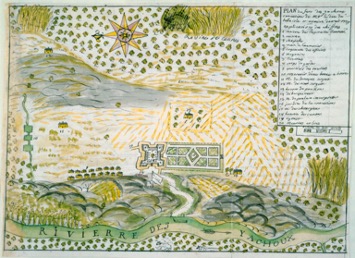

Fig. 2.Hand drawn map depicting the environs of “habitations eloignées.” Source: Jean-François-Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, Plan du Fort des Yachoux, concession de Mgr. le duc de Belle Isle et associex, detruit, 1729, [1747], map no. 6. Courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library.Notes

-

See “Fleuriau Demands Death for Maroons,” Keywords for Black Louisiana, published on August 9, 2024, https://docs.k4bl.org/keywords/d0254.html. ↩

-

Elizabeth Ellis, “The Natchez War Revisited: Violence, Multinational Settlements, and Indigenous Diplomacy in the Lower Mississippi Valley,” The William and Mary Quarterly 77, no. 3 (2020): 441-72; Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992), 106-111. The French use of the term “Bambara” carried varied meanings across time and space. At Saint-Louis and Gorée on the Senegambian coast, the French employed the term to describe enslaved soldiers working for the Company of the Indies. As the Segu Bamana state expanded around 1712 under the leadership of Mamari Kulibali, those identified as Bambara by the French increasingly included ethnic Bamana people forced into the slave trade as a result of slave raids in the region. For more on this history, see Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 96-100; Jessica Marie Johnson, Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 38; Boubacar Barry, Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade (London: Cambridge University Press, 1998). ↩

-

Of the twenty-three recorded slave voyages to arrive from Africa in French-controlled Louisiana, twenty-two of the total twenty-three ships arrived between 1719 and 1731. The last ship, the St. Ursin, arrived in August 1743, with 190 survivors from Senegambia. ↩

-

- Keywords:

- crime & punishment fugitivity imprisonment marronage seizure translator violence la traversée Middle Passage resistance

- Latitude:

- 30.0125

- Longitude:

- -90.0603

- Documents:

- d0295 d0296 d0297